A hand-written letter from Cuba arrived at the desk of the director of the American Occupational Therapy Association, where I’d been working for more than eight years. Passed on to me to translate because of my Spanish fluency, the writer, Armando Hernández, explained that he suffered from a rare disease that had already destroyed one kidney and most of the other. He had undergone at least five surgeries in Cuba. “Please help me, my life is in your hands,” the letter pleaded. “I’m only 23, just beginning to live, but now facing death. Friends with my condition have already died, often painfully.” Just to stay alive, he said he needed medications unavailable in Cuba, so had given up his job as a medical equipment technician to spend every waking moment sending out appeal letters to foreign organizations listed in a medical library. His illness, he explained in subsequent correspondence, was a recessive hereditary kidney disease, cystinuria. Both his parents carried the gene, but didn’t manifest the condition, nor did his brothers or young son. I could easily have trashed the letter, not even addressed to me, but instead, I replied, “Querido Armando,” Dear Armando.

Having lost my older son in an accident and my foster son to AIDS, I felt compelled to try to save this unknown young man. Sending money would have been easiest, but Cuba didn’t have the meds. By calling around to pharmacies, I discovered that the medications were rare, but could be ordered with a doctor’s prescription on a prepaid basis, since a pharmacy would not ordinarily carry them. Next task was finding a physician willing to write prescriptions for a patient living in another country. I finally located a sympathetic Latin American doctor working at an international organization. I bought a month’s supply for $300 and found a reliable traveler to Cuba to deliver it. Month after month, that cost became increasingly burdensome given my limited means as a single mother, as well as a risky investment, easily lost at any step along the way. I begged Armando to find other benefactors, but the few who responded to his appeals proved unreliable. Once I’d started sending him the medications, in all good conscience, I dared not stop, since his life depended on them.

Finally, I told Armando that I couldn’t keep supplying his medications ad infinitum. Already nearing retirement age and with my own family responsibilities, I simply could not sustain a continuing outlay of $300 a month and assure reliable delivery. If I should become sick or die, his lifeline would be cut off. He would simply have to come to the U.S. He agreed, as anxiety and uncertainty about his medications weighed on him constantly.

I’d already been denied a humanitarian visa to the U.S. for Armando, so now I obtained a letter of invitation for him from a kindly pastor living in Mexico. Using the letter, I advise him to apply for a Mexican visitor’s visa, promising to pay his roundtrip air fare and fees. After discarding the return ticket, he was then to cross the U.S. border asking for asylum, usually granted to Cubans actually stepping onto American soil. His parents and young son, who lived with him, were reluctant to see him go, but agreed.

In 1998, Armando finally got his exit visa, flew to Mexico, and discarded his return ticket as planned. At the border at Matamoros, he plunged into the Rio Grande and swam across, balancing his lone suitcase on his head, a veritable “wetback.” He touched American soil on the other side and soon obtained asylum.

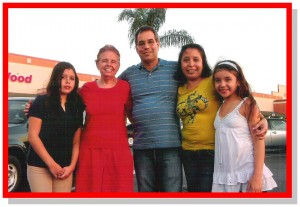

Thanks to a combination of proper medications and a low-protein diet, Armando is successfully managing his illness. He specializes in repairing complicated hospital machinery, showing a quick grasp of modern technology. Married and with two adorable step-daughters, he is now a U.S. citizen. He also brought his namesake son to this country. Now, at age 74, when I make my annual visit to Honduras for projects I still have there, I stop by Miami on the return trip to visit Armando and his family. A short letter, written in Spanish and mailed to an unknown person years ago, resulted in saving a young man’s life and enriching my own.

==================================================

Barbara E. Joe, a freelance writer and Spanish interpreter and translator, lives in Washington, DC, and is the author of Triumph & Hope: Golden Years with the Peace Corps in Honduras.

A REMINDER that we can help each other

THANK YOU for sharing this wonderful story! Refreshing, uplifting and an inspiration to all of us to help each other.